I couldn’t sleep, so in between catching up on some anime I hit Twitter. And what did I find there? My pals hashing the hell out of #YASaves, a hashtag directed squarely at none other than the Wall Street Journal, in response to this piece by Meghan Cox Gurdon. Snip:

Pathologies that went undescribed in print 40 years ago, that were still only sparingly outlined a generation ago, are now spelled out in stomach-clenching detail. Profanity that would get a song or movie branded with a parental warning is, in young-adult novels, so commonplace that most reviewers do not even remark upon it.

This is what happens when you put an op-ed rant in a book review column. Ms. Cox Gurdon does summarize a number of young adult books, but the title of the piece is “Darkness Too Visible,” and the permalink is called “Book Review: Young Adult Fiction.” However, the piece is pure opinion, and as such it’s no different from this very blog entry. It doesn’t evaluate the works in any depth, or from any contextual standpoint aside from “This isn’t like Louisa May Alcott and I don’t like it!” And that’s all well and good when you’re having low blood sugar on Livejournal, but it’s not aesthetic critique.

This is unfortunate, because Ms. Cox Gurdon is making a point that Michel Foucault made decades ago about culture. Naming a pathology makes it real and grants it the opportunity to flourish within the discourse, where it can then be normalized within a culture. Ms. Cox Gurdon explains the process with less theory jargon here:

Yet it is also possible—indeed, likely—that books focusing on pathologies help normalize them and, in the case of self-harm, may even spread their plausibility and likelihood to young people who might otherwise never have imagined such extreme measures. Self-destructive adolescent behaviors are observably infectious and have periods of vogue. That is not to discount the real suffering that some young people endure; it is an argument for taking care.

But here’s the thing about “pathologies”: they’re not always sicknesses. They’re often just ways of being which our culture has yet to find the right words for. And that’s what writing is: the quest for the right word. Anyone who writes, whether badly or well, contributes to that quest. They carry the torch that little bit further. Like scientists conducting tiny variations of the same experiment over decades, they slowly build up new definitions of the reality we have always inhabited. That is their task. It is not an easy one, and it is not made any easier by vultures circling above, shrieking at those on the path to please stop, they don’t want to fly any further in pursuit.

Let’s not forget that fiction for young adults has always been edgy. It is just as troublesome and confusing as the characters that inhabit it. Ms. Cox Gurdon contends that forty years ago, YA as a genre didn’t exist. Perhaps my math isn’t right, but To Kill A Mockingbird was published (and won the Pulitzer) in 1960, and continues to be a classic of young adult literature. It deals with rape and incest and racism. And you’re fucking well right there are a lot of swear words in it. And no, it’s not terribly uplifting. It’s a wonderful story about familial and neighbourly love, but it ends with two acts of police corruption and outright murder.

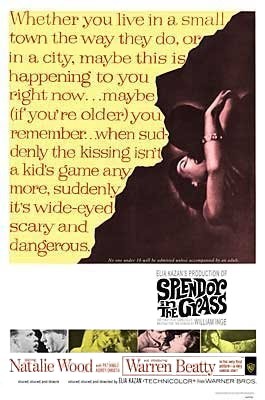

Maybe we should look to film for examples:

Oh. Maybe not.

I have no doubt that Ms. Cox Gurdon is writing for the tastes of her readers, including those who follow her column at the Washington Examiner, where she writes about being a mother to five children, and how she occasionally wishes that automobiles would be replaced by their 17th Century forebears, the horse and buggy. I have no doubt that those readers are fine, upstanding Americans who care deeply about the state of literature. My hope is that those readers donate to their libraries on a regular basis, that they consistently vote for levies that improve literacy among youth and the underprivileged, and that they rail against tax cuts that would diminish budgets for education. But judging by the other columns I saw at The Examiner, I doubt that’s what’s happening. As a paper, it trends socially conservative. And that’s fine. The anvil that is the Constitution of the United States of America can bear the heat of free speech, even when that heat is more like the inflammation of an arthritic joint.

But no writer, and no paper, and no culture, is in the position to tell our youth who or what they are. That’s their own quest — finding the right words to answer those questions, and finding new words when the old ones aren’t big enough. Because no matter what label we ascribe to our youth, the only thing we know they are for sure is this: they are changing.