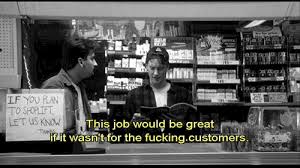

A while ago, I tweeted something based on this piece in VICE UK, called “Things You Only Know When You’ve Worked in Retail.” I don’t really care for the clickbaity title, but the content of the piece isn’t wrong. Here’s what I said:

People ask me how I do gritty, lived-in SF and futures work and I basically always answer: “I used to work retail.” https://t.co/P2ugdAlf8m

— Madeline Ashby (@MadelineAshby) July 3, 2015

That got retweeted around, and I heard a lot of agreement from people who had worked front-line service jobs. From baristas to booksellers, they agreed with Bertie Brandes’ core thesis, which was that “until you’ve repeatedly thrown up from acid reflux in the Covent Garden American Apparel changing rooms as you pathetically spritz the mirrors with window cleaner, you can’t really say you know what real life is.”

I started my first retail job when I was sixteen. I was careful to say that I’d be seventeen, soon. This made the exhausted women at my local thrift store look at the five-foot, 98-pound girl in front of them who could barely lift a gallon jug of milk a bit more favourably. But I wasn’t high and I didn’t steal and I spoke Spanish, so they liked me. My arithmetic was terrible — my end-of-night count was always a horrorshow — but I wasn’t mean. (That came later, after more retail work. When I was green, I was sweet.)

Working retail — or any job that forces you to deal with the general public on a face-to-face, hand-to-hand level — is an out-of-bubble experience. Unless you’re working a job your parents got you, or a job a friend got you that is also mostly populated by friends, or you spend a lot of time volunteering, it’s possibly the first time you’ve had to cater to the needs of others wildly different from yourself. Thanks to the Internet (and gerrymandering, and redlining, and strategic school-districting), we spend more and more time with people whose tastes, circumstances, and demography reflects our own. It’s a social filter bubble. An echo chamber. Working retail pops that bubble faster than you can say “How can I help you?”.

When I worked at the thrift store, I met people I never would have interacted with otherwise. Not just my co-workers, but the customers. There was the Japanese guy who bought all our Levi’s and sold them overseas. (Once he had five whole shopping carts full of jeans, and screamed at his wife when she didn’t line them up right.) There was the little baby with no feet, whose mother let her crawl along on her shins through the toy aisle. (She was the happiest child I’d ever met, in retail or any other context.) There was the middle-aged white man who obsessed over a real leather bullwhip we had in the display case, asking me once a week at least to take it out so he could stroke it, and always buying used issues of Playboy instead. (The Playboys were also in the display case, meaning I stayed there watching him flip through them. There was a stool behind the case, though, so that was nice. Later I saw him at an art gallery event in downtown Seattle, and quietly told my friend that we needed to leave. To his credit, my friend didn’t question me, and got me out of there. Now he’s my best man at my wedding.) By the way, that guy did buy the bullwhip. During the semi-annual half-off sale.

But it also works the other direction, depending on your prior experience. For one summer and one Christmas retail season, I worked at a Talbots competitor specializing in women’s suiting, where I regularly took care of Janie Hendrix. You know, Jimi’s sister? Yeah. She was a far cry from my former clientele. And as a middle class kid from unincorporated King County, I would possibly never have had a sense of how a woman of her station lives, without that job. (For the record, Janie was very nice, and we always looked forward to her visits. And not just because it took care of commission for a week.)

Later, I worked at a vitamin store on Long Island. I met queer vegans and servicemen on leave and Muslim women looking for halal Vitamin E. I watched my first theft, as a co-worker, his skin ruined by steroids, stuffed endless amounts of zinc and creatine into a bag. I listened as a woman wearing silver and turquoise jewelry told me that it was important everybody eat healthy, “because the people in Congress, they don’t want us to be strong, when the uprising happens — they don’t want us to be able to fight back.”

All these experiences helped me as a fiction writer. That’s largely because writing fiction — good, believable, engaging fiction — is about depicting people as they are. And you learn a lot about people as they are — unvarnished, strained, worried, needful — when your job is interacting with them on a daily basis. There’s the woman who just wants to get pregnant, so bad, and she tells you this as she picks up a bottle of pre-natal vitamins just in case. There’s the woman whose ex-boyfriend is getting off parole soon and she’s deciding between buying a winter coat for her kid or paying to change the locks. You tell these women to talk to their doctors. You tell them to talk to the police (because you’re young and stupid and don’t know yet how these women are fucked over, systemically). You come to realize that you are literally the safest person for them to talk to, because your interaction is so proscribed, so limited. Everyone else in their lives can shit on them, but you can’t. They come to you for kindness because you’re being paid to be kind.

This is also where I get tired with “grimdark” or “gritty” books/series/films/media where “gritty” or “realistic” just means “all rape all the time.” Because rape is a terrible thing, but there are other terrible things that happen over the course of a life that are terrible in different ways. There’s living in your car because your parents kicked you out. There’s paying a over two hundred dollars a month for L-theanine/St. John’s Wort/5-HTP/melatonin/magnesium supplements because you don’t have health insurance and can’t afford SSRIs. There’s losing your kids because you didn’t make the meetings and buying them someone else’s old toys at 9:30 at night on December 23rd because that’s when the check came. There’s systemic poverty. There’s a twenty-week abortion restriction. There’s a police officer shooting you dead because you had the audacity to reach inside your pocket. If you’re trying to think of something “gritty” and “realistic” to happen in your fictional world, and the only thing you can think of is rape, then you probably haven’t spent a whole lot of time in the real, gritty world. You probably aren’t much acquainted with the many and varied forms of human suffering there are. You’ve probably had it pretty easy. That, or you just want somebody to get their tits out. Maybe that’s it.

Working retail has also helped in my foresight career, and writing science fiction prototypes for corporate clients. Much of foresight is thinking about how people already use technology. How they interact with touchpoints. User stories and user journeys. Customer personae and end-user profiles. Executing a marketing strategy on the ground that customers will respond to. If you want to think like customers, then you have to work with customers. You have to observe them in their natural habitat. The sanctimonious complaints of piracy in media over the past ten years have originated largely from people who never interact with customers. Because people who have interacted with customers can tell you that stuffing twelve ads in front of a movie, and forcing at-home audiences to put up with twenty different clicks before they can see it, is not a desirable customer experience. It’s why Netflix and Apple TV and Hulu have succeeded while $3.99 DVDs are in an impulse-buy bin at Wal-Mart. This isn’t always a moral wrong. It’s just a blindspot. And it happens everywhere, in every industry.

Because your end user is not really a character in a flat-pack future. Your end user is a person: unvarnished, strained, worried, needful. Your end user doesn’t give a shit about you. They just want the thing/platform/service they bought to work right the first time. Apple didn’t succeed just because they manufactured beautiful pieces of hardware and performed seamless acts of software. They succeeded because customers want things to work out of the box. Because they have other shit to do. Their whole lives are not about enjoying your offering. Their whole lives are about your offering enhancing their enjoyment. It is not about you. It will never be about you.

And that’s what you learn, working retail. That it’s not about you. That the customer will not necessarily choose the most logical option. That they have their own needs. You can herd them, incentivize them, influence them. But that’s all you can do. Because if you’ve been designing solely for single white men ages 18-34, you don’t get to be surprised when literally everyone else has different needs, desires, and habits, and uses your product or service or platform differently as a result. You can mine their data all you want, but if you can’t empathize with them, then you’re bound to fail somewhere along the line. Numbers aren’t feelings. Information isn’t context. Emotional labour is hard work, and empathy is an inherently creative act that requires imagination. So the next time you imagine the future, imagine with empathy. The customer isn’t always right. But they’re almost never a copy of you.