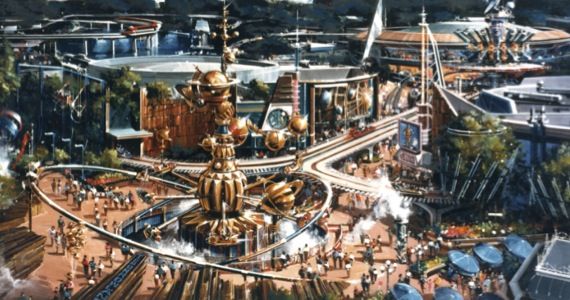

This review of Disney’s Tomorrowland (and others like it that I have read) got me thinking about something I was asked at the Design In Action summit last week in Edinburgh. I was there participating in the “Once Upon a Future” event, where I read a story called “The Dreams in the Bitch House.” It’s about a tech sorority at a small New England university. And programmable matter.

After I did my keynote and read my story, I did a Q&A. After a few questions, someone in the audience asked: “Why so negative?”

I get this question a lot. I’ve been involved in a couple of “optimistic” science fiction anthologies, namely Shine (edited by Jetse de Vries) and Hieroglyph (edited by Kathryn Cramer and Ed Finn). But people don’t invite me to these because I’m an optimistic person. In fact, it’s usually quite the opposite. Evidence:

When I was trained as a futurist (I have a Master’s in the subject), I was taught to see the whole scope of a problem. That’s at the root of design thinking. The old joke about designers is that when someone asks how many designers you need to change a lightbulb, the designer asks “Does it need to be a lightbulb?” Because really, what the room needs is a window. When people talk about innovation, that’s what they mean. A re-framing of the issue that helps you see the whole problem and approach it from another angle.

America’s problem is not that it needs more jetpacks. Jetpacks are not innovation. Jetpacks are a fetish object for retrofuturist otaku who jerked off to Judy Jetson, or maybe Jennifer Connelly’s character in The Rocketeer. “We were promised jetpacks!” they whine. Yeah, dude, but what you got was Agent Orange. Imagine a Segway that could kill you and set your house on fire. That’s what a jetpack is.

Jetpacks solve exactly one problem: rapid transit. And you know what would help with that? Better transit. Better telepresence. Better work-life balance. Are jetpacks an innovative solution to the problem of transit? Nope. But they sure look great with your midlife crisis.

But railing against jetpacks isn’t an answer to the question. Why so negative? Three reasons:

1) We have more data than we used to, and we’re obtaining more all the time.

Why don’t we fantasize about life in space like we used to? Because we know it’s really fucking difficult and dangerous. Why don’t we research things like food pills any more? Because we know eating fibre helps prevent colon cancer. We know those things because we’ve done the science. The data is there, and for every piece of technology we use, we accumulate more. It’s hard to argue with that vast wealth of data. At least, it’s hard to do so without looking like some whackjob climate change denier.

2) Less optimistic futures have the power to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

When people ask me, “Why can’t you be more positive?” what I hear is, “Why can’t you tell me a story that conforms to my narrative and comforts me?” Because discomfiting futures have real power. As Alf Rehn notes:

What we need, then, is more uncommon futurism. A futurism that cares not a whit about what’s hot right now, who remain stoically unimpressed by drones and wearable IT, and who instead take it as their job to shock and awe CEOs with visions as radical as those of the futurists of yore. We need futurism that is less interested in agreeing with contemporary futurists and their ongoing circle-jerk, and who takes pride in offending and disgusting those futurists who would like to protect the status quo.

The truth is that the horrible dystopia you’re reading about is already happening to someone else, somewhere else. What makes people nervous is the idea that it could happen to them. That’s why I have to keep sharing it.

3) The most harmful idea in this world is that change is impossible.

Octavia E. Butler said it best: “The only lasting truth / is Change.” And yet, we act like change is impossible. Whether we’re frustrated by policy gridlock, or rolling our eyes at Hollywood reboots, or taking our spouses on the same goddamn date we have for for twenty years, we act as though everything will remain the same, forever and ever, amen. But look around you. Twenty years ago, thinks were very different. Even five years ago, they were different. Look at social progress like gay marriage. Look at the rise of solar power. Look at the shrinking of the ice caps. Things do change, they are changing, and they will change. And not all of those changes will be positive. Not all of them will be negative, either. But change does occur. Rather than thinking of change as a positive or a negative, as utopian or dystopian, just recognize that it’s going to happen and prepare yourself. Futurists don’t predict the future. We see multiple outcomes and help you prepare for them.

In the end, the lacklustre performance of Tomorrowland at the box office has nothing to do with whether optimism is alive or dead. It has to do with changing demographics among moviegoers who know how to spot an Ayn Rand bedtime story when they see one. There are whole generations of moviegoers for whom jetpacks don’t mean shit, whose first memories of NASA are the Challenger disaster. And you know what? Those same generations believe in driverless cars, solar energy, smart cities, AR contacts, and vat-grown meat. They saw the election of America’s first black president, and they witnessed a wave of violence against young black men. They don’t want the depiction of an “optimistic” future. They want a future where their concerns are taken seriously and humanely, with compassion and intelligence and validation. And that’s way harder than optimism.

Great stuff, spot on.

I’ll probably see Tomorrowland out of a sense of duty. The lines should be short, with everyone lining up to see Fury Road again.

“… and they witnessed a wave of violence against young black men.”

It’s not a wave of violence against young black men. It’s a wave of white people finally *noticing* violence against mostly-but-not-entirely young, mostly-but-not-entirely male blacks. This “wave” of violence has been going on for *centuries*.

Oh, I agree. I just think there’s been a shift in the availability of evidence of that wave of violence. Reading about something in history books or newspapers, or hearing about something in a community or from parents and grandparents is a lot different, as an experience, from watching it on YouTube (or experiencing it in person, obviously). I think (or I want to think) that it’s tougher for kids who have never been victimized by police to look at those videos and say it’s not happening.

Maybe I’m reading the page wrong, but the link you provided that eating fiber prevents colon cancer actually says that eating more fiber has no significant effects on preventing cancer, and there’s only one study that sort of implies that. Whether or not that’s true, I’m not sure that having so much more data means more than we have more data; there’s only a few things that we actually have conclusive evidence on, and if your look at a lot of these studies in detail there are very reductionist and are only make tiny, highly qualified claims. Extrapolating from those claims to make sweeping conclusions doesn’t actually improve things, it’s the same sort of a appeal to a different authority. It can just be used as another sort of mythical belief.

Pingback: Futurist Madeline Ashby On Optimism Onscreen: “No One Cares About Your Jetpack” « Movie City News

Superb! Nicely done.

Michael