Good question. Glad you asked. If you pre-ordered the book, know two things: a) I’m ever so grateful, and b) it won’t arrive on time. Why is that? My fellow Angry Robot author Kameron Hurley explains it succinctly:

So back in June Angry Robot Books, publisher of THE MIRROR EMPIRE, closed its ancillary imprints, Exhibit A and Strange Chemistry. This was part of a wider cost-cutting exercise initiated by Osprey, Angry Robot’s parent company, which was going up for sale along with Angry Robot. Angry Robot has since pushed out its fall releases while wheels turn behind the scenes on this. Now you know about as much as I do about that, all of which is public knowledge.

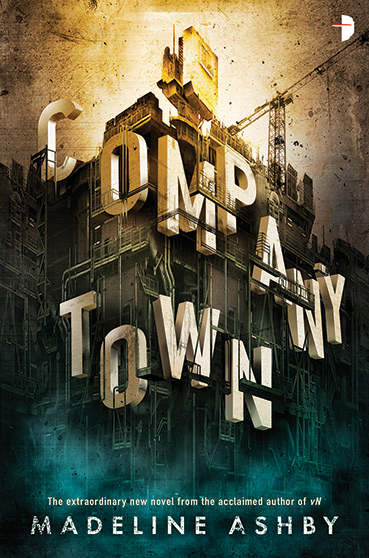

Now, about those fall releases that were pushed out. Company Town is on that list — it won’t be coming out September 30th. And that’s a good thing. Why? Because it has yet to be edited.

As Kameron accurately points out, business comes to a halt when the mergers and acquisitions are afoot. By the time I sent in my manuscript, things had already rolled to a stop. That manuscript still needs some tender loving care. (Don’t we all?) That means everything is going to take longer. It might be a long time before you read the whole thing. But I’d rather you wait a while to read a good book than let you plunge headlong into something riddled with errors, inconsistencies, contrivances, missteps, leaden prose, and the thousand natural flaws that a novel is heir to.

But, because you’ve been so patient, here’s a big ol’ chunk of it.

***

Underneath all the birdshit and saltscars, the architecture of the docking platform was still grand: huge arches left over from some other investor’s future, all straight and white and minimalist. Now they were a dingy grey, like most everything else on the rig. People stretched a long way down the catwalks leading up to the platform. Most of them were young and exhausted-looking, like they’d stayed up all night planning something. Their skin was still greasy from the night before, and they were all sharing droppers with each other.

“You want?” one of them asked. She was a very pale girl with a bald head and a huge mandala spanning her gleaming skull. It glowed and pulsed along with her heartbeat, barely visible. The whole bioluminescent inkjob trend really didn’t work for white people. Not enough contrast.

“I’m fine.” She just didn’t much like the next client, that was all. Or rather, the client of the next client. There would be no excuse to hit him unless he acted up. It was probably wrong to hope that he would. Still.

“Going to the handoff?”

“Hadn’t planned on it.” Hwa watched the other girl’s eyes carefully. No nervous flickering gaze. She had no specs. Contacts? She obviously couldn’t see Hwa’s true face. But her friends could. Their gazes kept landing on it and then flicking away, as though to make sure that the stain was still there, that it wasn’t a trick.

“I just don’t think Lynch is the best solution for this community,” the girl said. “You know they’re just gonna flip it. Just take this whole town apart and sell it for scrap. That’s what they’ve been doing with every other rig-burg they buy.”

“They might.” Hwa leaned over the rail. The early September sun was already hot at this early hour. She yearned for winter, when no one would look twice at her long sleeves.

“Doesn’t that, like, concern you?”

It did. Hwa tried to avoid thinking about it. If the number of roughnecks dipped below a certain level, then New Arcadia couldn’t justify paying the agency that employed Hwa and Sunny. The union would take care of them for a while, but eventually the agency would have to place them elsewhere. Maybe St. John’s. Maybe — God forbid — Calgary. If she wound up there, she’d have to consider carrying a gun. And she hated guns. But that was only if Lynch flipped the rig.

“They wouldn’t have bought this place if they didn’t think of it as an asset.” Hwa watched the maglev slide into place above them. It too came from somebody else’s future: a smooth fibreglass one where every machine looked a bit like a dolphin. Was New Arcadia really an asset? Maybe now was the time to follow all the other companies right the hell out of here. The line started to move. “I’ll worry about it more when they make some kind of announcement.”

“But we have a chance to influence them right now!” the girl said. She blinked furiously in Hwa’s direction. Then she did it again. Four times, with an earnest stare at the end.

“She doesn’t have any eyes,” one of the girl’s friends said. He winced just looking at Hwa. “You have to give her something…real.”

“What? Really? No way.” The girl closed her eyes tightly, waited a beat, and then opened them again. When she did, her mouth fell open. Her hand raised to cover it. She had seen Hwa’s true face, without any Mind Your Manners filters. Now she couldn’t help but stare. “Oh,” she said, finally.

“He’s right,” Hwa said. “I don’t have any eyes. Not like yours, anyway.”

“Do you…” She looked absurdly hopeful. “Do you have glasses?”

“Nope.”

The low-tech experience was obviously behind her comprehension. She knew Hwa was poor, now. She knew that whatever test might have warned Sunny about the baby she was carrying had been either ignored or unfinished. What she didn’t know that the only reason she could see Hwa’s face at all was that Sunny had missed the twelve-week cutoff and had to keep her. That Sunny had even talked about giving her up, until the girl behind the desk at the agency’s adoption arm talked her out of it. Because nobody would want Hwa. Not with a face like that. Not with Sturge-Weber, and its associated blindness and seizures and Christ knew what else. So Sunny should just try and be a good mother. After all, she obviously loved her little boy — the one she’d brought out to this city, this tower of flame and poison floating on a dead ocean — so very much. She just needed to try harder with Hwa. Really. The love would come. Eventually. Maybe.

“Does it…?”

“No,” Hwa said. “It doesn’t hurt.”

*

The Belle du Jour system said Eileen was currently at the end of the starboard side of Tower 2. Hwa was early. She pinged Eileen from the hallway and waited. People were mostly leaving. They ones with filters gave her no second glance; the ones without frowned at her and her empty halo of information. Hwa didn’t have a lot going, social-wise. And no implants meant no data, which meant no halo. Her stain did all the talking.

Outside the client’s apartment, another bodyguard was waiting. It was Big Fionn. He was a hugely fat man with a beard so long it had braids in it. Most of it was grey, by now. He was brushing crumbs out of it when Hwa arrived.

“Here all night, eh?” Hwa asked.

“And don’t you know it.” Big Fionn zipped up his leather jacket. It looked real. Hwa had no idea how he’d afforded it. Their salaries weren’t bad, but they weren’t great, either.

“You gonna be cool?”

“Huh?”

Big Fionn nodded at the door. “With him. You know. You need me to stay? ‘Cause I can stay.”

Hwa checked her watch. “No. You’re off. Go home. Sleep.”

He grinned, exposing a row of gold teeth. “That’s the magic word.”

And with that he was off. He lumbered off to the elevators. Hwa watched him hold the door for a woman carrying a baby. Then he ducked inside, and he was gone.

Five minutes later, Eileen was officially late. Hwa checked her watch. No answer. She checked the hallway. No big guys. No roughnecks. Nobody who would give her trouble if she was already in the process of making it for Eileen’s client. Ideal conditions.

Hwa spoke into her watch: “Belle, my safecall is late; proceeding to contact.”

There was a pause. “Keep us posted! Good luck!”

Hwa stood up, checked the hall again, and knocked on the door. Inside there was giggling, and a muffled, “I told you so!” Hwa rolled her eyes. The hallway was almost empty, now.

“It’s okay, Mr. Moliter,” she said to the door. “Nobody’s gonna see you.”

The door jerked open so fast he had to have been waiting for her. All these years later he was still a pallid, fishlike man, with a weird gawping mouth and almost colourless eyes and a puffy face constantly shadowed by stubble that looked more like blackheads than hair. He was also short, and he acted like it. Now was no exception.

“How dare you say my name out here?” he hissed. “What if somebody’s parents heard you? What if-” He blinked. He recognized Hwa. He shut up.

Hwa plastered a smile across her face. “Hi, Mr. Moliter,” she said in her cheeriest cute-Korean-girl voice. “How’s the eye?”

The scar across his right eyebrow twitched. He swallowed. Then he appeared to gather some dignity by closing his robe and standing a little straighter. “It’s fine,” he said. “Doesn’t bother me at all.”

“That’s real good to hear. So they re-attached the retina and everything, huh?”

Moliter licked his thin, raw lips. The man was dumb as a pike and twice as mean. He watched Hwa with one side of his face as he directed his voice into the apartment. “Eileen! Time to go!”

Eileen was still giggling. She bounced out of the apartment and made an I’m sorry face at Hwa. She looked fine: rich red hair in place, eyeliner expertly winged, no bruises, no funny walking, no tears in her stockings. She even squeezed Moliter’s hand.

“I had a great time,” Eileen said.

“Yeah. Great. Bye.” He shut the door.

Eileen turned to say something, but Hwa was already talking to her watch. “Belle, my safecall is accounted for. I’m taking her home, now.”

“Good job!” the watch said. “Have a nice day!”

“Thank you for knocking.” Eileen threaded one perfumed arm through Hwa’s. “Can we mug up? His coffee was terrible.”

“Teachers can’t afford the good stuff, eh?”

“I have fucked teachers with much nicer coffee. Hell, I’ve fucked tutors with better taste.” Eileen squeezed her arm. “Please? Can we stop? There’s a good spot on my floor.”

Hwa checked her watch. There was just enough time. “Sure.”

Eileen leaned over and looked at Hwa’s wrist. “Busy day?”

Hwa steered them into the queue for the elevator. “Not really. Slow night last night.”

Eileen cocked her head to the side and closed her eyes. There was an audible crunch in her neck. “Ugh. I’ve had that all night.” They hustled into the elevator, and Eileen leaned against the glass. The massive blades of the windmill whirling outside cast her in shadow briefly, and then revealed her again. On and on, dark and light, as the blades of the mill cut and cut and cut through the veil of morning mist.

“People are just saving their money,” Eileen said. “New sheriff in town, and all that.”

“It’ll be fine.”

Hwa hoped she sounded more certain than she felt. She honestly had no idea what the Lynch family would decide once they took ownership of New Arcadia. They could invite another agency in to encourage competition and bring down the hourly rates, or change up the fee-for-service model. Or they could be uptight about it and fire the agency, send all the sex workers scurrying back into massage parlours or whatever it was they used to pretend they did for money. And of course they could just shut the whole rig down, and watch the bottom fall out of every other business in the city once the roughnecks left. Lynch was still a privately-held corporation. They didn’t have to release any policy statements on the subject of their sexual broad-mindedness or their employment strategy or anything else that might concern the town they had just bought. Not until they chose to bring the hammer down.

She tried to smile. “Hey, if we have to move, at least you won’t have to fuck that fish-faced asshole again.”

Eileen rolled her eyes. “Sacred Heart of Christ, Hwa, he’s not that bad.”

The other people in the elevator were pretending not to overhear them. Hwa waited until the doors chimed open before ushering Eileen out of them.

“He’s a dick.”

“You know, you could go back to school. I asked him.”

Hwa pulled up short in the middle of the elevator court. “What?”

“I asked him. I asked if you could go back and finish. And he said you-”

“You talked about me? During your appointment?”

“Well, not during-”

“I have to go,” Hwa said. She made a show of checking her watch. “I’m sorry. I have to go to Tower Three. Boss wants to see me. Are you okay on this floor?”

Eileen sighed. “Sure.”

*

Nail spun the winch on the door. When it swung open, the smell of burnt sugar and saddle soap wafted through. They entered a circular space walled almost entirely in glass save for the door behind them. The space was completely underwater. Through the glass, the black waters of the Atlantic and whatever inhabited them was plainly visible. Right now, what inhabited them was a man in a breathesuit. He was chained to a shark cage.

“Oh, good, Hwa.” Mistress Séverine stood up. She wore a white silk robe that gleamed and rippled as she crossed the room to shake Hwa’s hand. Her grip was as ferociously strong as ever. Hwa could still feel the power in her hands through Séverine’s leather gloves.

“Ma’am.”

“Please sit. Nail, please bring another place setting. You will eat, won’t you?”

Nail disappeared into another room before Hwa could protest. She almost called out to him that he didn’t have to go to any extra trouble for her, but the kitchen door clanged shut behind him and she swallowed her words.

“Hwa, do sit. Please. And ignore the man in the cage. One of his neural implants started malfunctioning during his third tour. He asked me to help him re-experience fear. The process requires our complete disregard.”

Hwa found her seat on a low white sofa. Mistress Séverine resumed her club chair, which sat quite a bit higher. Hwa understood that the arrangement of the furniture was made to make clients feel like supplicants, but it was annoying for everyday business. She hunched forward.

“Don’t slouch, Hwa.”

She sat up straighter. “Yes, ma’am.”

“And take that hair out of your face. I like seeing people when I speak to them.”

Hwa tried to secure the left parting of her hair behind her ear. When she met Séverine’s gaze, the older woman smiled. “That’s better. Now. Let’s talk about how you left Eileen so abruptly this morning.”

Hwa’s mouth fell open. Séverine was still wearing her gloves, which meant she’d been on the job. Did she check the Belle de Jour system in the middle of appointments? Had Eileen pinged her?

“It doesn’t matter how I know, what matters is that I know,” Séverine said, as though having read Hwa’s mind. “I know you don’t like that man, Hwa, but you must finish the jobs you take. Anything else skews our metrics, and we live by our metrics.”

“I know-”

“Apparently, you don’t. Need I remind you that any unfinished safecalls count as demerits within the system? And that demerit points make us look less safe? Less reliable? Less professional?”

Hwa sighed. “No, ma’am.”

“You don’t need a reminder of that?”

She shook her head. “No, I don’t. I understand it.”

“So it won’t be a problem for you in the future?”

“No. It won’t.”

Séverine smiled brilliantly. “Good.” She turned her gaze to the kitchen door, and out walked Nail and Rusty, bearing a silver tea set and a tower of pastries on their respective trays. The men set each tray down silently and stood, staring at Séverine.

“Rusty, please tell Hwa about her breakfast.”

Rusty was Nail’s opposite: short where the other man was tall, talkative and not silent, gingery blonde and not dark. He gestured at each item as he described it. “Good morning. For breakfast you have Earl Grey tea, steamed egg custard with smoked salmon, laminated croissants with bakeapple filling, and goat’s milk yogurt topped with blueberry-verbena compote.”

“And the cannelles,” Séverine said.

“Yes. And cannelles, prepared with dark spiced rum, and lightly dusted with ginger-infused Demerara sugar. I do apologize for forgetting those.” He made little bows to both of them.

“It’s okay,” Hwa said. She cast a quick glance at Séverine. “I mean, it’s okay with me, anyway.”

Séverine began removing her gloves. “Thank you, Rusty. The two of you may leave. I’ll ring for you when we’re finished here.”

Both men bowed, and took their leave. Hwa reached for the teapot, but Séverine shooed her hand away. “I’ll pour. You may begin assembling your plate. The tongs are just there.”

The china Séverine favoured was so thin Hwa could perceive light through it. The sight of her own grubby fingers on it made her wince. She grabbed one of everything and waited for Séverine to finish pouring. Then she waited as the other woman took her time putting together her plate, unrolling her napkin, and choosing her cutlery. She weighed her spoon in her hand thoughtfully, as though evaluating a weapon.

“I have work for you today, Hwa.” Her spoon slid into the custard and along the edge of the ramekin to bring up a steaming lump of yellow flecked with pink. “Rusty and Nail are going to the handoff, and I want you to escort them.”

Hwa swallowed her yogurt. She had never been to the new platform. The town had voted to seal the old one up instead of repairing it, after it blew. It was part of why all the other companies were pulling out, and why Lynch could buy the town so cheap. What remained of the old platform waved half-heartedly from beneath the waves like a veteran waggling a stump at passersby. When the train swerved over it, she made sure not to look. If the dead caught you looking, they might start looking back.

“I understand if it’s difficult for you.”

“It’s not difficult.” She bit savagely into her croissant.

“And for this job, it will be necessary for you to escort the boys at a distance. Be as unobtrusive as possible.”

Hwa frowned. “Wait a second.” She hunched over her knees, slouching be damned. “You want me to spy-”

“Oh, hush. I’m not asking you to do anything untoward. Just follow them and make sure they’re safe, as with any other job.” Séverine watched Hwa over the rim of her teacup. “This town is changing, Hwa. My boys want to see that change happen. But I’ve already watched my share of trainwrecks.”

*

Hwa trailed Rusty and Nail as they exited the train car ahead of hers. Nail’s height made them easy to follow, even when they descended the stairs and into the crowd bottlenecked at the hastily-constructed security checkpoint. She pushed up a little closer to them as they went through — close enough to see if hands went to weird places, but not close enough for them to see her right away if they turned around suddenly. Nothing happened. The guy brushing his hands over Nail didn’t even ask him anything. Rusty ushered him through before the guard could change his mind. Good.

“Holy shit, Hwa.”

Hwa turned. The guard was a round guy with dishwater blond hair and a fresh sunburn in progress. He sat on a barstool down the fence, nursing a pouch of electrolytes. He put it down and stood before ambling over to her.

“Wade,” Hwa said.

“Not seen you in forever,” Wade said. “Where you to?”

Hwa nodded past the fence.

“What’re you at?”

Hwa repeated herself by nodding more deeply this time.

“Seriously?”

She shrugged.

“Well, fuck me. Thought you hated crowds.” He pronounced his th without any h, like taut.

“I don’t hate them,” Hwa said. “But I’m on the job, so…”

“The job?” Wade’s eyebrows rose. “You’re, uh…in the family business, now?”

Hwa wasn’t sure she could muster an eyeroll epic enough for this assumption. She sighed. “No, Wade, I’m not here to fuck anybody. I’m here to watch somebody. Two somebodies. I’m a bodyguard. Now am I free to go, or what?”

Wade pinked right up, deepening his sunburn. “Jesus, I’m sorry, Hwa, I didn’t-”

“I don’t have to take some lecture on the family business from somebody wearing that logo.” She jabbed one finger into the new white Lynch patch on Wade’s jacket. She stared at him hard. “How long has your dad worked this rig, Wade?”

Wade looked away. His eyes searched the ground for a moment. When he spoke, he mumbled. “I only thought, with your brother gone, maybe-”

“Wade.” Hwa ducked under his downcast gaze and made sure he was looking her in the eye.

“Can I go through, or not?”

He looked like he might say something. He even put his hands up, like he wanted to pat her down. But then his hands fell and his shoulders sank and his breath deflated, and he said: “Sure. Go on through.”

The new platform afforded good views of the other towers and their windmills. There was her tower, Tower One, the oldest and most decrepit with grimy capsule windows jutting out at pixel intervals, and Tower Two, all glass bubbles and greenery piled like a stack of river rocks, and Tower Three, made of biocrete and healing polymers, Tower Four gleaming black with solar paint, and Tower Five, so far out on the ocean that it was easy to forget it was even there. It had been designed by algorithm, and its louvers shifted constantly, like a bird fluffing its feathers up against the cold. Occasionally this meant getting a sudden blinding flash of glare when the train zipped past it, or when a water taxi approached its base. Hwa’s old Municipal History teacher said the designers referred to the towers as Metabolist, Viridian, Synth, Bentham, and Emergent. There was an extra credit test question on it, once. Mr. Ballard wrote her a nice note with a smiley face in the margin when she got it right. Now she couldn’t seem to get rid of that little factoid.

From the sky, she heard the guttural churn of a chopper homing in on the platform. As one, the crowd surged closer to the stage. Rusty and Nail must have moved with them, because she saw no sign of them at the edges of the crowd.

Then the explosions started.

They began as a high whistle. Then a bang. Firecrackers, maybe. Acid green smoke rose above the crowd. Some people fell to the ground. Others ran. Someone ran past Hwa and knocked her down. She rolled over into a crouch.“RUSTY!” Maybe Rusty and Nail had fallen down, too. She couldn’t see through the rush of legs and green smoke. The smoke itself was thickening, spreading, moving. A group of people stood under the centre of the cloud, moving their hands like old people doing tai chi, shaping the smoke. In the shadow cast by the smoke, Hwa saw the pulsing glow of a mandala tattoo.

The kids from the platform. They had done this. From her crouching position, Hwa saw them deploy a swarm of flies that projected words against the smoke: TAKE BACK YOUR TOWN. LYNCH THE LYNCHES.

“Oh, for Christ’s sake,” Hwa muttered. “RUSTY! RUSTY, CAN YOU HEAR ME?”

She stood up. Maybe they had run away. She hoped they had run away. Far away. Already, she heard sirens. NAPS saucers buzzed low across the sky. What was she going to tell Séverine? She had to find them. She needed higher ground. Through the veil of green fog, she caught a glimpse of the caution yellow stairways she knew led up toward the refinery.

She ran.

She ran as though she were running away, far to the edge of the crowd, keeping her head down, ducking behind a wastebin as the first wave of NAPS officers in riot gear washed across the platform. After they passed, she made for the gate to the staircase. It was locked with only a rusting sign and a corroded chain. She kicked it open and started climbing.

From the first tier of the catwalks, she saw only the fog. It was rising, now, and she pushed on and up another tier. From that second tier, she saw the fringes of crowd. NAPS kettling the cloud. People already zip-tied to each other. She looked for Rusty’s hair next to Nail’s tall body.

Nothing. She kept running.

On the stairs to the third tier, she saw the man with the rifle.

He paced the refinery catwalks high above the fray. As Hwa watched, he paused and began examining the rifle. Hefting it in his hands. Peering down the scope. The gun was illegal on the platform; since the fall of the Old Rig there were laws against projectiles and explosives and all the other things that could cause a pillar of fire to vaporize a crew of roughnecks like tobacco leaves. Not that that mattered, in this long and terrible moment. What mattered was that he could shoot into the crowd. What mattered was her promise to protect two men in that crowd.

The chopper was louder, now, closer. Who was he with? The riot cops? The protesters? Was he going to shoot the Lynches, or was he going to shoot into the crowd? Maybe he’d had his eyes done. Probably. He would be sharper than she was. Faster. The only thing she had going for her was the ability to surprise him.

She felt the air whumping on her sternum as the chopper hovered, seemingly unwilling to land. It was hard to swallow. From behind a girder, she watched as the man rested his rifle on the railing. His eyes remained on the chopper. He snapped open a shoulder-rest on the rifle. She gauged the length of the catwalk. She had fifteen feet by three, with a four foot clearance on the railing. All her kicks would have to be three- and four-pointers aimed at the head. Steel grate, no purchase for her feet. The man was six feet tall or just under it. She would have to jump to make up the difference.

Well, that was one way of surprising him.

When he reached into his pocket, she rushed him. He must have felt or heard her feet clanging across the steel, because he looked up: blue eyes, ginger hair, deep lines, mouth open. He gripped the rifle and swung it toward her; it was the opening she needed. She batted the business end of the weapon and pushed it down and away, then turned around as though to run. Her navel met her spine, her right knee met her chest, and her left foot pivoted to rise. Her body became a pendulum. Her eyes met his just before her heel crunched into his nose: he looked oddly hurt, as though he were confused at this sudden imposition of violence, at the rudeness of it.

Then he was really and truly hurt, and bleeding everywhere.

“Fuck!”

Hwa grabbed for the gun. He wouldn’t let it go. Blind and bleeding, he gripped it crosswise with both hands and shoved it at her face. She had to bounce backward. His head jerked; he was listening for her feet on the steel. Hwa yanked the gun towards herself anyway. He refused to let go.

“I’m not going to hurt you,” he said through the blood.

“I know you’re not,” Hwa said, and ducked under the gun to plant her right leg behind his left and throw her weight at his thighs. He tumbled backward and then she was on him, locking her ankles and squeezing her thighs as she dug an elbow into his stomach and tried to pry the gun away.

“Fuck it,” he muttered. He tossed the gun aside. It went off: a quick burst of fire that turned into screams down below. They both froze. They looked at the gun, then each other. His eyes were even bluer now with all the blood in them.

“You fucking idiot!” Hwa punched him straight in the mouth. Pain scraped across her knuckles.

“I didn’t know!” His hands caught her wrists. He had a terrific grip. “I thought it was-”

“It’s a fucking oil refinery, you asshole!” She flipped her hands over to break his hold. “It’s fucking explosive!”

But he was sitting up and staring, not listening. Hwa watched his gaze flick over her shoulder. She turned. Above them, against the hazy blue of the sky, as thin silver disc. A flying saucer. As she watched, a single laser began painting her skin.

Beneath her, the man shouted: “No, wait, stop, don’t-”

Then the pain started.