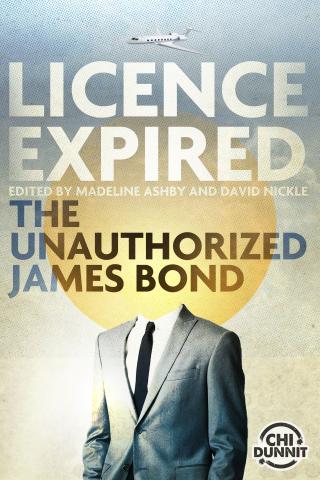

The Table of Contents for my anthology with David Nickle, Licence Expired: The Unauthorized James Bond is now available. (You can pre-order it here.) I’m extremely proud of all the stories we included. It’s my first anthology, and there are stories by Charles Stross, Robert Wiersema, Kelly Robson, EL Chen, Jacqueline Baker, and others. These writers bit into the Bond mythos with sharp teeth, and they drew blood. Public domain — such as Ian Fleming’s Bond books and stories are, in Canada — grants great freedom in the arts, and that freedom can be intimidating. But you wouldn’t know it, reading these stories.

With that said, we wish this TOC were more diverse. We wish we’d heard from more people from more types of backgrounds, with more interpretations of Bond and his world. And because including more voices in publishing is an ongoing process with an ongoing conversation surrounding it, I thought I’d share what we learned from this particular experiment.

You have to ask for the diversity you want. Ask early. Ask often.

We made it a special mission to request women writers and writers of colour whose work we enjoyed to participate in this anthology. Overwhelmingly, they were flattered to be asked, but felt no particular kinship with James Bond as a character, or the world Fleming created. Or the deadline was too tight for them. Or they were already too busy with other projects and commitments. I’ve had the privilege of working with editors who ask for stories a whole year in advance, but in our roles as editors, David and I didn’t have that luxury. We are quite literally racing against changes to Canadian copyright legislation. We could only include the writers who could keep our pace. But we know we could have asked earlier, worked more contacts, pushed harder.

The narrower the prompt, the narrower the field.

James Bond is a recognizable character with specific canonical attributes. The way Fleming wrote him and the way his filmmakers interpreted him are subtly but noticeably different, and the chasm between the two expands as time passes. It’s one thing to ask writers to take on the idea of “James Bond” that has transcended transmedia: the cinematic Bond, the videogame Bond, the comic book Bond. It’s another thing altogether to ask a writer to familiarize herself with Fleming’s works and situate her own work alongside them. Writers who had never read Fleming before got in touch with us to express surprise at the content — at the rape, the racism, the general cruelty and callousness of the character, and also the addictive quality of the prose, the breathtaking speed with which Fleming could turn a simple concept into a ripping yarn. Despite inhabiting a culture wherein Bond is the subject of parody on shows like Archer and films like Austin Powers, they had never met the man before. And adhering to Fleming’s characterization of him imposed a real set of limitations, a tight space in which to do a big job. The process of editing this anthology was not the same as editing something with a wider genre focus, like “space opera” or “sexy vampires” or “the weird” (whatever the fuck that is — it used to be “slipstream,” and before that it was “magic realism,” and before that it was “literature”). We cut great material because it directly referenced the films. We had to. It sucked.

James Bond isn’t “for” everybody. That’s why Idris Elba needs to play him next.

Or Chiwetel Ejiofor. Or Daniel Henney. Or Arjun Rampal. Or Julien Kang. Basically anyone from this list. Like it or not, the Bond films are what lead people to the Bond novels, and the Bond films are overwhelmingly about a white guy protecting Western hegemony from non-white, non-Western interests. Sure, there are people of colour who help Bond out, but at no point have the films said, “Hmm, perhaps the people most likely to be stopped and searched by London police officers have something to offer our national security apparatus at its highest levels.” That was part of what made Elba’s Luther series so interesting. It said that you could have the wrong look and the wrong accent and hell, the wrong attitude, and still make a real contribution to public safety and criminal justice. (Kingsmen: The Secret Service also told this story, but about white kids wearing black fashions.) I could explain this in greater detail, but Junot Diaz has already explained it beautifully:

“You guys know about vampires? … You know, vampires have no reflections in a mirror? …If you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. And growing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all. I was like, “Yo, is something wrong with me? That the whole society seems to think that people like me don’t exist?” And part of what inspired me, was this deep desire that before I died, I would make a couple of mirrors. That I would make some mirrors so that kids like me might see themselves reflected back and might not feel so monstrous for it.”

Take it from the guy who won the Pulitzer. And even if you don’t believe in the rightness of broader representation, consider the business case. There’s a reason that the Fast and Furious movies break box-office records: they’re cracking good action movies with a diverse cast that brings a diverse crowd. There’s somebody for everybody in the audience to root for. Finding an under-served market and serving it is Business 101. There are untapped audiences out there for whom almost nothing is being created. Lose the bigots, and you’ll gain a wider audience. If bigotry were good for business, Amazon and Wal-Mart would still be selling Confederate flags. If bigotry were good for business, Reddit would have learned how to make a profit by now. The cinematic James Bond has been blond and black-haired, short and tall, thick and lean. It’s okay for him to be brown, too. Or queer. Or to say that once upon a time, he was called Jane. If audiences stuck by James Bond after Moonraker, they will stick by him if he changes colour.

Live and let die.

You would think that in the fifty years since Bond emerged, all his stories would have been told. That is emphatically false. What have been told are the same types of stories, increasingly recursive re-tellings of tales past, like traumatic memories recalled in the comfortable confines of narrative therapy. But when you let other people tell the story, especially people whose voices have historically been kept silent, the material suddenly feels fresh again. This is how you re-invigorate a franchise. It doesn’t mean letting go of all the nostalgia, but it does involve creating new memories for another generation of fans. There’s a balance to be struck while working with a beloved character, between telling an interesting new story and keeping the things we love about him or her intact. These writers did it. Other writers, working with other iconic characters, can do the same. As we face an era of almost continous reboots, sequels, prequels, tentpoles, and seamless transmedia franchises, it’s important to realize that the only way to keep the machine running is to feed it new blood once in a while. That’s what we’ve tried to do here, and the results are stunning.